Tuesday, December 11, 2007

THE TOOLMAKER’S OTHER SON

A Memoir by Galen Green

First typed draft copyright 2005 by Galen Green

All Right Reserved

(Prose text begun on November 14, 2005; 3:00 a.m.; typed draft begun on December 4, 2005; 12:45 p.m.; Kansas City, Missouri

Ecclesiastes 9:16

Table of Contents

1. Contents

2. Acknowledgements

3. Preface

4. Prologue with Jigsaw Puzzle

5. The Willows (1830 – 1949)

6. Wichita (1949 – 1972)

7. The Deep South (1967)

8. Mexico (1968)

9. New York (1969)

10. Rural Kansas (from 1830 on)

11. Cambridge (1972)

12. Boston (1972 – 1973)

13. Salt Lake City (1973 – 1974)

14. Columbus (1974 – 1981)

15. Out West (1976)

16. Tick Ridge (1980)

17. Philadelphia (1981 – 1982)

18. Park City (1983 – 1984)

19. Seminary (1983 – 1984)

20. Wichita Redux (1984 – 1990)

21. Kansas City (from 1990 on)

22. Brookside (1990 – 1998)

23. The Ambassador (from 1998 on)

24. Chestnut Circle (from 1992 on)

25. Wichita Revisited (2002)

26. Everywhere & Nowhere

27. Afterword

28. Appendices (A – Z)

29. Notes

30. Index

31. About the Author

Preface:

Mission Statement

Of The

Institute for Mythoklastic Therapy & Research

i.

Ecclesiastes 9:16 says it best. The wisdom of the poor is despised. I submit my life’s work as a case in point.

But it’s not about me. It’s about what’s most in need of fixing. Lip service on this topic abounds, so pay it no heed. Decide for yourself. What price are you willing to pay to be even a tiny part of the solution, instead of a part of the problem?

When we strip away the agreed-upon lie we call The Real World, what we’re left with is the real world, which coincides chillingly with the wisdom of the poor referred to by the wise little Jew who wrote Chapter 9 of Ecclesiastes and who just happens to be my personal role model and hero.

We here at the Institute for Mythoklastic Therapy & Research (I.M.T. & R.) honor and seek the wisdom of the poor. But doing so requires us to expose as an enslaving bamboozlement the ostensible “wisdom” of the majority. And this is where the trouble begins. For Mythoklastic Therapy & Research poses a threat to those whose livelihood is the slave trade.

ii.

Given the world we’re given, what might we say, with any accuracy, is going on here? No, I haven’t driven our car off the road and into the ditch of philosophication. Heavens forefend! Rather, I’ve attempted to point out the Bethlehem star upon which history has taught us to rely to guide us through this darkness. And were we simply three wise folk traversing afar, debate would be unnecessary. But we’re not.

The night sky is filled with bright little dots and it seems at times that each of us is following a different one. Yet even this would be preferable to the tragic reality of who’s following what for what I cannot help but see – and therefore cannot help but paint for you here – is a nest of ninnies following what isn’t even there.

Slavery has been the cornerstone of human civilization – and still is. But in recent centuries slavery has needed mythocracy to fire its boilers and cover its tracks. Hence, this folly, this con game, this bamboozlement whereby most folks chase after black holes.

iii.

Perhaps what led Plato to his notion of there being another world, a parallel universe, a reality hidden inside of another dimension and completely apart from the one we think we see, was nothing more than his ordinary daily interactions with the people around him.

Certainly, that’s what’s done it for me, as well as for numerous others much smarter than me. Everyday conversation, especially, leads me there, time and again. When I hear the words and phrases we use to describe this world we share, I’m reminded of how mistaken we are, how paltry our beliefs, how inaccurate our supposed “understanding.”

Even if this were the totality of what Plato and I have in common, it would make me want to go back and study him more closely, him and his most influential imitator, Saul of Tarsus, alias Saint Paul. But that’s a subject for another day, another book. Today, here with you, I’m in the mood to explore how it is that things are so seldom what they seem. It’s my personal belief that the reason for this is not that there is a world of the “spirit” lurking here in this room with us, but rather that we have been coerced into lying to ourselves and to each other about what is actually going on here in this world we share.

-- Galen Green, Founder & C.E.O., Institute for Mythoklastic Therapy & Research; autumn 2005______________________

Prologue with Jigsaw Puzzle

(An Open Letter to Kai Li & An Mei)

My Dearest Children,

As I sit down to write this, it is just a few days before Thanksgiving, and you are still two precious little girls full of promise and still too young for any of this have much meaning.

When I was the age that you are now, I was not at all fond of hearing those words: “When you are older.” They tended to make me feel that I was being belittled with the reminder that I was not yet something that I was supposed to be. Please believe me when I assure you that it is not my intention to make you feel that way. You are exactly what you are supposed to be – two precious little girls full of promise.

Likewise, when you are older and reading this, you will be exactly what you are supposed to be, and I will most likely be dead and gone. In that sense, I am today like the insects of autumn which I observed out in the garden, laying their eggs which will hatch next spring when they themselves have returned to dust, or who, in some cases will serve to furnish their offspring’s first meal. Take. Eat. This is my body – these few words that follow – broken for you and for many.

It will always be the fate of those of us who write these sorts of things to never meet those who will read our words, just as the insects laying their eggs out in the autumn garden will never know their own little ones, just as the parents who brought me into the world never knew me, just the parents who brought you into the world have never known you. Ours is the story of adoption, yours and mine. And it is a very good story, as happy a story as human destiny seems capable of providing; though it is a story which remains mysterious and even unsettling to those around us who have not experienced it.

But we can talk more about that later. Suffice it to say for now that I may well be speaking to you now from beyond the grave, trying to get an urgent message to you, one which I am feverishly scribbling at the end of some doomed civilization. Think of it as a message of love and hope and warning, sent forth to you here with my promise to you that, if you both to decipher it, you just might find to come in handy.

ii.

Try to think of this as a sort of scrapbook. (Do people still keep scrapbooks?) Try to think of this as a gathering together of the scattered fragments of a picture of a story, one which might begin like this:

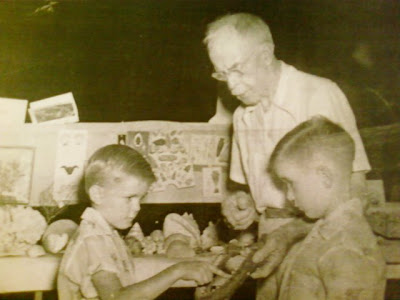

Once upon a time, a toolmaker had two sons. This poor but honest toolmaker lived with his plain but virtuous wife and their two sons in a rather proud (though shabby) hovel on the edge of The Great American Desert, which also happened to be on the edge of what turned out to be a new age, a new reality.

Now, of the two sons, one was this way and the other was that way. And the reason that I put it in these terms is that I myself just so happen to be the son who was this way and do not wish to offend or alienate my brother, who just so happened to be the son who was that way. And let’s leave it at that. I’m sure that all parties involved will quite understand.

Anyway, try to think of this as a scrapbook of what happened both before and after this story of this picture which just so happened to open in the way I have just described. OK?

Now, this next sentence, which just so happens to have become the sentence you are now reading (or listening to, as the case may be) is the sentence in which time travels very quickly so that, hour by hour, the years fly by like the fluttering pages of a calendar in one of those old movies out of the 1940’s, the practical result being that the poor but honest toolmaker’s two sons are now, as the saying goes, all grown up. And, as Fate would have it, the younger (and taller) of the two lads has grown up to marry the right damsel with whom he has had the right children and has gone about doing all the right sorts of things in the right house in the right neighborhood, etc. But this scrapbook you’re holding in your hands at this very moment does not happen to be a gathering together of the scattered fragments of a picture of the story of that particular son, but rather the etc. etc. of this son, the other son, the toolmaker’s other son – me.

Now, if you’ve ever had the delicious pleasure of putting together what we used to call a jigsaw puzzle containing, let’s say 5,786 pieces, then you already know the bittersweet thrill of puzzling over where, precisely, you ought to begin. One thing that makes pretty good sense, of course, is to begin by clearing off a large space on the living room carpet. (Do people still use words like “living room” and “carpet” in the world of the future?)

Anyway, once a goodly sized space has been cleared, then we may begin thinking about how we wish to begin putting together our enormous puzzle of, say, 5,786 brightly colored pieces. There they are, “jumbled in one common box,” as a very good poet named W. H. Auden once put it. What in the world are we to do but to close our eyes and reach blindly into this box of 5,786 brightly colored pieces of our puzzle and, without peeking, pull out the first piece of our enormous puzzle, placing it, ever so strategically (which here means arbitrarily) as closely as possible to the geographic center of this ample space we’ve cleared here on the living room carpet for our purpose. And, Bingo! There it is!

Alrighty, then. So what do we see? By golly, it looks like a song! A song! But how can that be? You lean over to peer into the puzzle box, at the 5,785 brightly colored pieces still jumbled together there, waiting to be picked, when suddenly you realize that each and every piece of this puzzle appears to be either a song or a poem or a letter to someone you’ve never heard of or what looks to be some fragment of furiously scribbled writing, like a daily entry in someone’s private diary or journal. How odd!

“What kind of jigsaw puzzle is this, anyway?” you ask yourself. The answer to this question is, of course, that this is that kind of jigsaw puzzle whose purpose is to eventually be folded up, just so, and turned, as if by magic, into this very scrapbook you find yourself holding in your hands at this very moment. Very clever; eh? Very!

But back to the living room carpet. Since you have, indeed, put together other puzzles in the past, you naturally resort at this point in the process to that tried and true stratagem of examining box containing the remaining 5,786 pieces to see if there might be a picture of the picture which will eventually emerge before your very eyes, here on the space you’ve cleared on the living room carpet, once all the pieces have been assembled.

But, alas, no such miniature representation of the final picture toward which we are working is to be found anywhere on or in or near the box in which the remaining pieces are jumbled. And yet it’s not as if no such final image were there in the box to be had, as could be said of those aggravatingly impossible puzzles, which we’ve all come across at one time or another, in which every single piece is exactly the same color as every other piece in the box, so that one’s effort at piecing them together would result, not in some interesting picture, but merely in a vast monochromatic field of red or black or white or – if one were very luck – blue.

Quite the contrary. The kind of jigsaw puzzle this appears to be is the kind upon whose every single brightly colored piece is printed something or other which your humble servant, the toolmaker’s other son, has considered to be worth including in our jigsaw puzzle that’s to eventually be folded this way and that until it’s been neatly folded up, just so, into this memoir of sorts, this scrapbook which I’ve put together here to give to you when you grow up.

So, here we are, down our hands and knees on the living room carpet, just the three of us (or so it seems), our eyes fixed upon this first brightly colored piece of our jigsaw puzzle, lying all alone there in the geographic center of this ample space we’ve cleared here for our purpose. But as we lean over, our heads nearly pressed together, in an effort to decipher what this first piece of our puzzle is trying to say to us, here is what we see; here is the song we see it singing to us:

{insert: “The World Is Ugly, and the People Are Sad” by Galen Green}

“Whew! What a way to start out a scrapbook!” you exclaim, reeling backwards in horror. “I thought scrapbooks were supposed to be pretty things!”

“Pretty is as pretty does,” I smile. “At least that’s what my mother used to say – my adoptive mother, who was, as we’ve already established, plain but virtuous.

“Where in the world did a song like that come from?” you ask, still trying to catch your breath.

“That’s an excellent question,” I reply. “I appreciate your asking it, and I’ll do the best I can to answer it. As with all of my songs, ‘The World Is Ugly, and The People Are Sad” is what used to be called a folksong.”

“What do you mean, ‘used to be?’”

I mean that the term “folksong” originally applied to any of a wide variety of songs born out of the experiences of those folks who were unlucky enough to find themselves living their entire lives at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. This usually meant that such songs had to do with hard luck or hard work or similar difficult circumstances or with what clinicians such as your father often refer to as “situational anxiety,” which is the most natural, healthy and perfectly understandable response to grinding poverty and to the hellish prison of optionless slavery inevitably resulting from it.

In other words, folksongs used to be about the lives of “the folk,” because they were songs born out of the life experiences and the candid observations of “the folk.” Any particular song was or was not a “folksong,” in other words, because of who wrote it (or, back before poor folks were allowed to learn to write, because of who first made it up and sang it).

Nowadays, however, the term “folksong” has come to refer most often to a song which has the sound or feel or flavor of those songs born out of the experiences of the poor folks of some earlier era. With all due respect, such songs might more accurately be called “faux folksongs,” not because they lack sincerity or authenticity of sentiment, but because they represent some relatively comfortable songwriter’s impression of the experiences and observations of the poor, rather than the real deal. A song such as “The World Is Ugly, and The People Are Sad,” on the other hand, represents the real deal, because it’s been written and sung by someone who is genuinely poor, someone whose harassed penury has been poured into it. It’s a folksong because it was written and sung by a poor person, a person whose life circumstances have been relatively uncomfortable in the socioeconomic dimension.

“But it doesn’t sound like a folksong,” you politely protest.

What I hear you saying is that it doesn’t resemble the type of songs we’ve all come, in the past half century or so, to think of as folksongs. But “The World Is Ugly, and The People Are Sad” isn’t a folksong because of what it resembles (i.e. because of what it sounds like), but because of who wrote it (i.e. because of whose actual life experiences and observations it represents, expresses and is born out of).

“But it’s so depressing. It’s so negative,” you interject. “I mean, where’s the hope? Where’s the redemptive love?”

The hope, as you put it, is in the acceptance of reality. And the redemptive love is there as well. But let’s not get bogged down in semantics. I promise you that we can revisit these issues later on, if you’re still in the mood for it. Let’s go back, instead, to your

A Memoir by Galen Green

First typed draft copyright 2005 by Galen Green

All Right Reserved

(Prose text begun on November 14, 2005; 3:00 a.m.; typed draft begun on December 4, 2005; 12:45 p.m.; Kansas City, Missouri

Ecclesiastes 9:16

Table of Contents

1. Contents

2. Acknowledgements

3. Preface

4. Prologue with Jigsaw Puzzle

5. The Willows (1830 – 1949)

6. Wichita (1949 – 1972)

7. The Deep South (1967)

8. Mexico (1968)

9. New York (1969)

10. Rural Kansas (from 1830 on)

11. Cambridge (1972)

12. Boston (1972 – 1973)

13. Salt Lake City (1973 – 1974)

14. Columbus (1974 – 1981)

15. Out West (1976)

16. Tick Ridge (1980)

17. Philadelphia (1981 – 1982)

18. Park City (1983 – 1984)

19. Seminary (1983 – 1984)

20. Wichita Redux (1984 – 1990)

21. Kansas City (from 1990 on)

22. Brookside (1990 – 1998)

23. The Ambassador (from 1998 on)

24. Chestnut Circle (from 1992 on)

25. Wichita Revisited (2002)

26. Everywhere & Nowhere

27. Afterword

28. Appendices (A – Z)

29. Notes

30. Index

31. About the Author

Preface:

Mission Statement

Of The

Institute for Mythoklastic Therapy & Research

i.

Ecclesiastes 9:16 says it best. The wisdom of the poor is despised. I submit my life’s work as a case in point.

But it’s not about me. It’s about what’s most in need of fixing. Lip service on this topic abounds, so pay it no heed. Decide for yourself. What price are you willing to pay to be even a tiny part of the solution, instead of a part of the problem?

When we strip away the agreed-upon lie we call The Real World, what we’re left with is the real world, which coincides chillingly with the wisdom of the poor referred to by the wise little Jew who wrote Chapter 9 of Ecclesiastes and who just happens to be my personal role model and hero.

We here at the Institute for Mythoklastic Therapy & Research (I.M.T. & R.) honor and seek the wisdom of the poor. But doing so requires us to expose as an enslaving bamboozlement the ostensible “wisdom” of the majority. And this is where the trouble begins. For Mythoklastic Therapy & Research poses a threat to those whose livelihood is the slave trade.

ii.

Given the world we’re given, what might we say, with any accuracy, is going on here? No, I haven’t driven our car off the road and into the ditch of philosophication. Heavens forefend! Rather, I’ve attempted to point out the Bethlehem star upon which history has taught us to rely to guide us through this darkness. And were we simply three wise folk traversing afar, debate would be unnecessary. But we’re not.

The night sky is filled with bright little dots and it seems at times that each of us is following a different one. Yet even this would be preferable to the tragic reality of who’s following what for what I cannot help but see – and therefore cannot help but paint for you here – is a nest of ninnies following what isn’t even there.

Slavery has been the cornerstone of human civilization – and still is. But in recent centuries slavery has needed mythocracy to fire its boilers and cover its tracks. Hence, this folly, this con game, this bamboozlement whereby most folks chase after black holes.

iii.

Perhaps what led Plato to his notion of there being another world, a parallel universe, a reality hidden inside of another dimension and completely apart from the one we think we see, was nothing more than his ordinary daily interactions with the people around him.

Certainly, that’s what’s done it for me, as well as for numerous others much smarter than me. Everyday conversation, especially, leads me there, time and again. When I hear the words and phrases we use to describe this world we share, I’m reminded of how mistaken we are, how paltry our beliefs, how inaccurate our supposed “understanding.”

Even if this were the totality of what Plato and I have in common, it would make me want to go back and study him more closely, him and his most influential imitator, Saul of Tarsus, alias Saint Paul. But that’s a subject for another day, another book. Today, here with you, I’m in the mood to explore how it is that things are so seldom what they seem. It’s my personal belief that the reason for this is not that there is a world of the “spirit” lurking here in this room with us, but rather that we have been coerced into lying to ourselves and to each other about what is actually going on here in this world we share.

-- Galen Green, Founder & C.E.O., Institute for Mythoklastic Therapy & Research; autumn 2005______________________

Prologue with Jigsaw Puzzle

(An Open Letter to Kai Li & An Mei)

My Dearest Children,

As I sit down to write this, it is just a few days before Thanksgiving, and you are still two precious little girls full of promise and still too young for any of this have much meaning.

When I was the age that you are now, I was not at all fond of hearing those words: “When you are older.” They tended to make me feel that I was being belittled with the reminder that I was not yet something that I was supposed to be. Please believe me when I assure you that it is not my intention to make you feel that way. You are exactly what you are supposed to be – two precious little girls full of promise.

Likewise, when you are older and reading this, you will be exactly what you are supposed to be, and I will most likely be dead and gone. In that sense, I am today like the insects of autumn which I observed out in the garden, laying their eggs which will hatch next spring when they themselves have returned to dust, or who, in some cases will serve to furnish their offspring’s first meal. Take. Eat. This is my body – these few words that follow – broken for you and for many.

It will always be the fate of those of us who write these sorts of things to never meet those who will read our words, just as the insects laying their eggs out in the autumn garden will never know their own little ones, just as the parents who brought me into the world never knew me, just the parents who brought you into the world have never known you. Ours is the story of adoption, yours and mine. And it is a very good story, as happy a story as human destiny seems capable of providing; though it is a story which remains mysterious and even unsettling to those around us who have not experienced it.

But we can talk more about that later. Suffice it to say for now that I may well be speaking to you now from beyond the grave, trying to get an urgent message to you, one which I am feverishly scribbling at the end of some doomed civilization. Think of it as a message of love and hope and warning, sent forth to you here with my promise to you that, if you both to decipher it, you just might find to come in handy.

ii.

Try to think of this as a sort of scrapbook. (Do people still keep scrapbooks?) Try to think of this as a gathering together of the scattered fragments of a picture of a story, one which might begin like this:

Once upon a time, a toolmaker had two sons. This poor but honest toolmaker lived with his plain but virtuous wife and their two sons in a rather proud (though shabby) hovel on the edge of The Great American Desert, which also happened to be on the edge of what turned out to be a new age, a new reality.

Now, of the two sons, one was this way and the other was that way. And the reason that I put it in these terms is that I myself just so happen to be the son who was this way and do not wish to offend or alienate my brother, who just so happened to be the son who was that way. And let’s leave it at that. I’m sure that all parties involved will quite understand.

Anyway, try to think of this as a scrapbook of what happened both before and after this story of this picture which just so happened to open in the way I have just described. OK?

Now, this next sentence, which just so happens to have become the sentence you are now reading (or listening to, as the case may be) is the sentence in which time travels very quickly so that, hour by hour, the years fly by like the fluttering pages of a calendar in one of those old movies out of the 1940’s, the practical result being that the poor but honest toolmaker’s two sons are now, as the saying goes, all grown up. And, as Fate would have it, the younger (and taller) of the two lads has grown up to marry the right damsel with whom he has had the right children and has gone about doing all the right sorts of things in the right house in the right neighborhood, etc. But this scrapbook you’re holding in your hands at this very moment does not happen to be a gathering together of the scattered fragments of a picture of the story of that particular son, but rather the etc. etc. of this son, the other son, the toolmaker’s other son – me.

Now, if you’ve ever had the delicious pleasure of putting together what we used to call a jigsaw puzzle containing, let’s say 5,786 pieces, then you already know the bittersweet thrill of puzzling over where, precisely, you ought to begin. One thing that makes pretty good sense, of course, is to begin by clearing off a large space on the living room carpet. (Do people still use words like “living room” and “carpet” in the world of the future?)

Anyway, once a goodly sized space has been cleared, then we may begin thinking about how we wish to begin putting together our enormous puzzle of, say, 5,786 brightly colored pieces. There they are, “jumbled in one common box,” as a very good poet named W. H. Auden once put it. What in the world are we to do but to close our eyes and reach blindly into this box of 5,786 brightly colored pieces of our puzzle and, without peeking, pull out the first piece of our enormous puzzle, placing it, ever so strategically (which here means arbitrarily) as closely as possible to the geographic center of this ample space we’ve cleared here on the living room carpet for our purpose. And, Bingo! There it is!

Alrighty, then. So what do we see? By golly, it looks like a song! A song! But how can that be? You lean over to peer into the puzzle box, at the 5,785 brightly colored pieces still jumbled together there, waiting to be picked, when suddenly you realize that each and every piece of this puzzle appears to be either a song or a poem or a letter to someone you’ve never heard of or what looks to be some fragment of furiously scribbled writing, like a daily entry in someone’s private diary or journal. How odd!

“What kind of jigsaw puzzle is this, anyway?” you ask yourself. The answer to this question is, of course, that this is that kind of jigsaw puzzle whose purpose is to eventually be folded up, just so, and turned, as if by magic, into this very scrapbook you find yourself holding in your hands at this very moment. Very clever; eh? Very!

But back to the living room carpet. Since you have, indeed, put together other puzzles in the past, you naturally resort at this point in the process to that tried and true stratagem of examining box containing the remaining 5,786 pieces to see if there might be a picture of the picture which will eventually emerge before your very eyes, here on the space you’ve cleared on the living room carpet, once all the pieces have been assembled.

But, alas, no such miniature representation of the final picture toward which we are working is to be found anywhere on or in or near the box in which the remaining pieces are jumbled. And yet it’s not as if no such final image were there in the box to be had, as could be said of those aggravatingly impossible puzzles, which we’ve all come across at one time or another, in which every single piece is exactly the same color as every other piece in the box, so that one’s effort at piecing them together would result, not in some interesting picture, but merely in a vast monochromatic field of red or black or white or – if one were very luck – blue.

Quite the contrary. The kind of jigsaw puzzle this appears to be is the kind upon whose every single brightly colored piece is printed something or other which your humble servant, the toolmaker’s other son, has considered to be worth including in our jigsaw puzzle that’s to eventually be folded this way and that until it’s been neatly folded up, just so, into this memoir of sorts, this scrapbook which I’ve put together here to give to you when you grow up.

So, here we are, down our hands and knees on the living room carpet, just the three of us (or so it seems), our eyes fixed upon this first brightly colored piece of our jigsaw puzzle, lying all alone there in the geographic center of this ample space we’ve cleared here for our purpose. But as we lean over, our heads nearly pressed together, in an effort to decipher what this first piece of our puzzle is trying to say to us, here is what we see; here is the song we see it singing to us:

{insert: “The World Is Ugly, and the People Are Sad” by Galen Green}

“Whew! What a way to start out a scrapbook!” you exclaim, reeling backwards in horror. “I thought scrapbooks were supposed to be pretty things!”

“Pretty is as pretty does,” I smile. “At least that’s what my mother used to say – my adoptive mother, who was, as we’ve already established, plain but virtuous.

“Where in the world did a song like that come from?” you ask, still trying to catch your breath.

“That’s an excellent question,” I reply. “I appreciate your asking it, and I’ll do the best I can to answer it. As with all of my songs, ‘The World Is Ugly, and The People Are Sad” is what used to be called a folksong.”

“What do you mean, ‘used to be?’”

I mean that the term “folksong” originally applied to any of a wide variety of songs born out of the experiences of those folks who were unlucky enough to find themselves living their entire lives at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. This usually meant that such songs had to do with hard luck or hard work or similar difficult circumstances or with what clinicians such as your father often refer to as “situational anxiety,” which is the most natural, healthy and perfectly understandable response to grinding poverty and to the hellish prison of optionless slavery inevitably resulting from it.

In other words, folksongs used to be about the lives of “the folk,” because they were songs born out of the life experiences and the candid observations of “the folk.” Any particular song was or was not a “folksong,” in other words, because of who wrote it (or, back before poor folks were allowed to learn to write, because of who first made it up and sang it).

Nowadays, however, the term “folksong” has come to refer most often to a song which has the sound or feel or flavor of those songs born out of the experiences of the poor folks of some earlier era. With all due respect, such songs might more accurately be called “faux folksongs,” not because they lack sincerity or authenticity of sentiment, but because they represent some relatively comfortable songwriter’s impression of the experiences and observations of the poor, rather than the real deal. A song such as “The World Is Ugly, and The People Are Sad,” on the other hand, represents the real deal, because it’s been written and sung by someone who is genuinely poor, someone whose harassed penury has been poured into it. It’s a folksong because it was written and sung by a poor person, a person whose life circumstances have been relatively uncomfortable in the socioeconomic dimension.

“But it doesn’t sound like a folksong,” you politely protest.

What I hear you saying is that it doesn’t resemble the type of songs we’ve all come, in the past half century or so, to think of as folksongs. But “The World Is Ugly, and The People Are Sad” isn’t a folksong because of what it resembles (i.e. because of what it sounds like), but because of who wrote it (i.e. because of whose actual life experiences and observations it represents, expresses and is born out of).

“But it’s so depressing. It’s so negative,” you interject. “I mean, where’s the hope? Where’s the redemptive love?”

The hope, as you put it, is in the acceptance of reality. And the redemptive love is there as well. But let’s not get bogged down in semantics. I promise you that we can revisit these issues later on, if you’re still in the mood for it. Let’s go back, instead, to your

The Toolmaker's Other Son

A Memoir by Galen Green

Copyright 2005, All Rights Reserved

Rough Draft; Installment #2 of 99

December 5, 2005

________________________________________

(Continued from Prologue with Jigsaw Puzzle; q.v.)

"But it's so depressing. It's so negative," you interject. "I mean, where's

the hope? Where's the redemptive love?"

The hope, as you put it, is in the acceptance of reality. And the redemptive love is there as well. But let's not get bogged down in semantics. I promise you that we can revisit these issues later on, if you're still in the mood for it. Let's go back, instead, to your original question, which was, if I recall correctly: "Where in the world did a song like that come from?"

The short answer is that it came from my life, from my experiences and observations. As the cartoonist Gahan Wilson so famously put it: "I paint what I see." But rather than let ourselves get even further sidetracked (That's an old railroading term which must be uniquely American, since I found it necessary to explain its origin to one of my very brightest non-American friends a few years ago.) By distracting debate as to the efficacy of my eyesight, please allow me to take you with me back to the beginnings of my experiencings and observings.

I'm willing to venture a wild guess that your getting to know a little bit about the bumpy, winding road that's brought me to these moments here with you will shed some valuable light on the puzzle pieces I've brought along with me to share with you in the pages of this scrapbook.

Chapter One: The Willows (1830 — 1949)

%%%%%%%%%%

"At the closing and razing of the Willows in 1969, records of its 64 years of

operation were piled in the back yard and burned. It was the end of an era."

— prairiebaby@hotmail.com

%

" . . . and our ancestors probably / were among those plentiful subjects / it

cost less money to murder."

— W. H. Auden, from "The Cave of Making," July 1964

i.

I was born in what was then referred to as a "hospital for unwed mothers" called the Willows, on the morning of April 30, 1949. At least, that's what they've led me to believe. The Willows, at 2929 Main Street, was a sort of rambling ranch- style brick mansion which sat atop Union Hill in Kansas City, Missouri, overlooking the historic Union Hill Cemetery, as well as Union Station and the passenger rail yards, with the downtown KCMO skyline glittering in the background. The World War I Veterans Memorial stood just across Mail Street, as did Saint Mary's Hospital, which later became part of Trinity Lutheran Hospital, where I worked as an armed Security Officer in the late 1990's.

Neither Hallmark nor Crown Center nor the Hyatt Regency to the north nor the thousand-foot broadcasting antenna looming up to the south, however, was as yet anywhere to be seen, back in 1949. Kansas City was still in its transitional phase of emergence out of what it had been in the wild and wooly era of the Pendergast machine, whose one positive bi-product, Harry S. Truman, had just been sworn in for what amounted to his second term as President of the United States. And as had been case on every April 30th for as long as anyone could remember, the lilacs were in bloom.

According to a web site I stumbled across on the Internet recently, the Willows (1905 — 1969) advertised itself in its brochure as being "a seclusion maternity sanitarium operated exclusively for the care and protection of the better class of unfortunate young women." A set of rough notes typed up by a social worker who'd evidently just finished interviewing my 25-year-old biological mother a few months prior to my birth tell us that I'd been conceived in or around my biological parents' small hometown (unnamed in the social worker's typed report) somewhere in north-central Indiana.

Since this set of notes was kept from me until I was nearly 50 years old, however, they played absolutely no role whatsoever in the formation of my identity. That is to say that, because the fact that, for example, the man and woman of whose genetic information I am the synthesis both served in the United States military during the Second World War was unknown to me until very recently, it served no meaningful function in shaping my understand of or self-definition of who I was, throughout my formative years.

The same holds true for any of the other facts typed into the social worker's rough notes, such as my bio-dad's being an Indiana farm boy of German-Irish extraction (and evidently the same size and shape that I myself was at his age) or my bio-mom's being a small-town beautician, also of German-Irish extraction, who said that she owned her own "beauty shop" (as they were called in those days), but whose stern Prussian father (whose stern mustachioed Prussian face I've often caught staring back at me from the mirror in recent years) would have (to put it in modern parlance) gone ballistic, had the shocking reality of my unsanctified advent in their little cosmos come to his attention.

Hence did my bio-mom concoct whatever plausible pretext she concocted, there in their little hometown somewhere in north-central Indiana, and took the train to Union Station in Kansas City and thence to a place called the Willows, perched there on that placid promontory, where she patiently awaited my tearful entrance onto this world's stage.

ii.

Meanwhile, a somewhat different drama was being played out in the childless home of the poor but honest toolmaker and his schoolmarm wife of seven years, 200 miles or so to the south in a city called Wichita, Kansas. Harry Green (1908 — 1982) and Margaret McCall Green (1912 — 1990) had grown up together and had known each other nearly all their lives, right up until that pleasant June day in 1941 when they'd been joined in holy matrimony (as some folks insisted on calling it), in her parents' tidy but somewhat cramped parlor in that little wood- framed house in the peaceful village of Richmond, Kansas, which would someday serve as the setting in dozens of my mid-life dream scenarios.

As my loving adoptive father, Harry, the toolmaker in the title of our story, explained it to me years later, he himself had been left "plumb sterile" as a result of his having somehow contracted, as a young, a case of "the mumps," and being unaware of the vulnerable position this had put him in, of his routinely jumping down off of a threshing machine during wheat harvest, thus causing these "mumps" to bring about in his organs of increase an irreversible inability to manufacture a sufficient quantity of healthy sperm to fertilize a female egg.

Besides his having been left "plumb sterile" by this unfortunate combination of circumstances (i.e. the adult case of "the mumps" and the extreme jarring of what we might delicately call his "male eggs," the incident carried with it, he told me, the instantaneous consequence of nearly murdering poor young Harry with an indescribably excruciating pain, ironically akin to the pangs of childbirth, as described by the women I've know who've survived to tell about it.

Or so Harry the toolmaker related the matter to me, his eldest son, years later, when I was perhaps 13 or 14 years old, and we were sitting alone together one evening on that dusty old broken couch, down in the musty unfinished basement of that little house on north Lorraine, having what both uncomfortable parents and uncomfortable adolescent children used to call "the talk," meaning that pre- revolutionary ritual of initiation into adult membership in the tribe of sexually repressed humankind in which the parent of (most often) the same gender as the adolescent child ritually, nervously and often inaccurately attempts to impart at least the rudimentary date concerning the intimate details of human reproduction.

I could tell that it was important to my adoptive father to share this revelation with me, so I tried to let me body language convey my gratitude for his openness. Much to my disappointment, however, this turned out to be the totality of what I was ever to know of why Harry & Margaret Green were unable to bring forth offspring from their own loins. I've often suspected that there may have been more to it than what was contained in my adoptive father's chivalrous official version; but now I'm old man, and those who could have shed any light on the matter have gone the way of all flesh.

Suffice it to say that the poor but honest toolmaker and his plain but virtuous wife loved one another with an admirable love and that each longed to have a child of their own flesh and blood who would be an integral part of their lives. Six months after they were married and had settled into their quaint but comfortable apartment on Waco Street near downtown Wichita, the Japanese military attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, so that Boeing Aircraft Company, where the toolmaker first earned his reputation as "The Toolmaker," was suddenly transformed into a booming industry, and Wichita began to flourish as never before — or since.

But as the toolmaker found his services increasingly in demand as a part of the war effort, his schoolmarm wife found herself increasingly alone at night, while the glowing stithy of aircraft assembly hummed night and day in the furious race to respond to the very real threat from foreign fascism which was hellbent to undo the noble democratic project known as the United States of America. And even

A Memoir by Galen Green

Copyright 2005, All Rights Reserved

Rough Draft; Installment #2 of 99

December 5, 2005

________________________________________

(Continued from Prologue with Jigsaw Puzzle; q.v.)

"But it's so depressing. It's so negative," you interject. "I mean, where's

the hope? Where's the redemptive love?"

The hope, as you put it, is in the acceptance of reality. And the redemptive love is there as well. But let's not get bogged down in semantics. I promise you that we can revisit these issues later on, if you're still in the mood for it. Let's go back, instead, to your original question, which was, if I recall correctly: "Where in the world did a song like that come from?"

The short answer is that it came from my life, from my experiences and observations. As the cartoonist Gahan Wilson so famously put it: "I paint what I see." But rather than let ourselves get even further sidetracked (That's an old railroading term which must be uniquely American, since I found it necessary to explain its origin to one of my very brightest non-American friends a few years ago.) By distracting debate as to the efficacy of my eyesight, please allow me to take you with me back to the beginnings of my experiencings and observings.

I'm willing to venture a wild guess that your getting to know a little bit about the bumpy, winding road that's brought me to these moments here with you will shed some valuable light on the puzzle pieces I've brought along with me to share with you in the pages of this scrapbook.

Chapter One: The Willows (1830 — 1949)

%%%%%%%%%%

"At the closing and razing of the Willows in 1969, records of its 64 years of

operation were piled in the back yard and burned. It was the end of an era."

— prairiebaby@hotmail.com

%

" . . . and our ancestors probably / were among those plentiful subjects / it

cost less money to murder."

— W. H. Auden, from "The Cave of Making," July 1964

i.

I was born in what was then referred to as a "hospital for unwed mothers" called the Willows, on the morning of April 30, 1949. At least, that's what they've led me to believe. The Willows, at 2929 Main Street, was a sort of rambling ranch- style brick mansion which sat atop Union Hill in Kansas City, Missouri, overlooking the historic Union Hill Cemetery, as well as Union Station and the passenger rail yards, with the downtown KCMO skyline glittering in the background. The World War I Veterans Memorial stood just across Mail Street, as did Saint Mary's Hospital, which later became part of Trinity Lutheran Hospital, where I worked as an armed Security Officer in the late 1990's.

Neither Hallmark nor Crown Center nor the Hyatt Regency to the north nor the thousand-foot broadcasting antenna looming up to the south, however, was as yet anywhere to be seen, back in 1949. Kansas City was still in its transitional phase of emergence out of what it had been in the wild and wooly era of the Pendergast machine, whose one positive bi-product, Harry S. Truman, had just been sworn in for what amounted to his second term as President of the United States. And as had been case on every April 30th for as long as anyone could remember, the lilacs were in bloom.

According to a web site I stumbled across on the Internet recently, the Willows (1905 — 1969) advertised itself in its brochure as being "a seclusion maternity sanitarium operated exclusively for the care and protection of the better class of unfortunate young women." A set of rough notes typed up by a social worker who'd evidently just finished interviewing my 25-year-old biological mother a few months prior to my birth tell us that I'd been conceived in or around my biological parents' small hometown (unnamed in the social worker's typed report) somewhere in north-central Indiana.

Since this set of notes was kept from me until I was nearly 50 years old, however, they played absolutely no role whatsoever in the formation of my identity. That is to say that, because the fact that, for example, the man and woman of whose genetic information I am the synthesis both served in the United States military during the Second World War was unknown to me until very recently, it served no meaningful function in shaping my understand of or self-definition of who I was, throughout my formative years.

The same holds true for any of the other facts typed into the social worker's rough notes, such as my bio-dad's being an Indiana farm boy of German-Irish extraction (and evidently the same size and shape that I myself was at his age) or my bio-mom's being a small-town beautician, also of German-Irish extraction, who said that she owned her own "beauty shop" (as they were called in those days), but whose stern Prussian father (whose stern mustachioed Prussian face I've often caught staring back at me from the mirror in recent years) would have (to put it in modern parlance) gone ballistic, had the shocking reality of my unsanctified advent in their little cosmos come to his attention.

Hence did my bio-mom concoct whatever plausible pretext she concocted, there in their little hometown somewhere in north-central Indiana, and took the train to Union Station in Kansas City and thence to a place called the Willows, perched there on that placid promontory, where she patiently awaited my tearful entrance onto this world's stage.

ii.

Meanwhile, a somewhat different drama was being played out in the childless home of the poor but honest toolmaker and his schoolmarm wife of seven years, 200 miles or so to the south in a city called Wichita, Kansas. Harry Green (1908 — 1982) and Margaret McCall Green (1912 — 1990) had grown up together and had known each other nearly all their lives, right up until that pleasant June day in 1941 when they'd been joined in holy matrimony (as some folks insisted on calling it), in her parents' tidy but somewhat cramped parlor in that little wood- framed house in the peaceful village of Richmond, Kansas, which would someday serve as the setting in dozens of my mid-life dream scenarios.

As my loving adoptive father, Harry, the toolmaker in the title of our story, explained it to me years later, he himself had been left "plumb sterile" as a result of his having somehow contracted, as a young, a case of "the mumps," and being unaware of the vulnerable position this had put him in, of his routinely jumping down off of a threshing machine during wheat harvest, thus causing these "mumps" to bring about in his organs of increase an irreversible inability to manufacture a sufficient quantity of healthy sperm to fertilize a female egg.

Besides his having been left "plumb sterile" by this unfortunate combination of circumstances (i.e. the adult case of "the mumps" and the extreme jarring of what we might delicately call his "male eggs," the incident carried with it, he told me, the instantaneous consequence of nearly murdering poor young Harry with an indescribably excruciating pain, ironically akin to the pangs of childbirth, as described by the women I've know who've survived to tell about it.

Or so Harry the toolmaker related the matter to me, his eldest son, years later, when I was perhaps 13 or 14 years old, and we were sitting alone together one evening on that dusty old broken couch, down in the musty unfinished basement of that little house on north Lorraine, having what both uncomfortable parents and uncomfortable adolescent children used to call "the talk," meaning that pre- revolutionary ritual of initiation into adult membership in the tribe of sexually repressed humankind in which the parent of (most often) the same gender as the adolescent child ritually, nervously and often inaccurately attempts to impart at least the rudimentary date concerning the intimate details of human reproduction.

I could tell that it was important to my adoptive father to share this revelation with me, so I tried to let me body language convey my gratitude for his openness. Much to my disappointment, however, this turned out to be the totality of what I was ever to know of why Harry & Margaret Green were unable to bring forth offspring from their own loins. I've often suspected that there may have been more to it than what was contained in my adoptive father's chivalrous official version; but now I'm old man, and those who could have shed any light on the matter have gone the way of all flesh.

Suffice it to say that the poor but honest toolmaker and his plain but virtuous wife loved one another with an admirable love and that each longed to have a child of their own flesh and blood who would be an integral part of their lives. Six months after they were married and had settled into their quaint but comfortable apartment on Waco Street near downtown Wichita, the Japanese military attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, so that Boeing Aircraft Company, where the toolmaker first earned his reputation as "The Toolmaker," was suddenly transformed into a booming industry, and Wichita began to flourish as never before — or since.

But as the toolmaker found his services increasingly in demand as a part of the war effort, his schoolmarm wife found herself increasingly alone at night, while the glowing stithy of aircraft assembly hummed night and day in the furious race to respond to the very real threat from foreign fascism which was hellbent to undo the noble democratic project known as the United States of America. And even

The Toolmaker’s Other Son

A Memoir by Galen Green

Copyright 2005, All Rights Reserved

Rough Draft; Installment #3 of 99; December 6, 2005

(Continued from Section ii. of Chpt. One: The Willows . . . . )

. . . . Waco Street near downtown Wichita, the Japanese military attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, so that Boeing Aircraft Company, where the toolmaker first earned his reputation as “The Toolmaker,” was suddenly transformed into a booming industrial complex, and Wichita began to flourish as never before – or since.

But as the toolmaker found his services increasingly in demand as part of the war effort, his schoolmarm wife found herself increasingly alone at night, while the glowing stithy of aircraft assembly hummed night and day in the furious race to respond to the very palpable from foreign fascism which was clearly hell-bent for the undoing of humankind’s noble post-enlightenment experiment in democratic government. And even though she may have kept her hands and heart busy throughout the daylight hours with the demands of teaching elementary school there in Wichita, those long lonesome nights of 1943 and 1944 and 1945, when the man she loved was far off in the darkness making the tools needed to build the B-17’s and the B-24’s and the B-25’s and the B-29’s needed to win that seemingly interminable set of overseas conflicts collectively known as World War II, served only to reinforce her longing for what she perceived to be the ascendancy unto the estate of motherhood.

And so it was that the toolmaker and the schoolmarm decided to adopt. The post-War Baby Boom helped. Every couple able to crank out a baby seemed to be doing so, whether inside or outside of wedlock. This included, of course, a certain young beautician and a forever-nameless farm boy up in some forever-nameless north-central Indiana hamlet, who got together one starlit night in the summer of 1948 to share their bodies with one another, thus setting our story in motion.

As of this writing, that three-block stretch of sidewalk which hugs the native stone retaining wall along the east edge Kansas City’s World War I Veterans Memorial Park and follows Main Street from Union Station up that hill to where the Willows once stood still consists of the very same cement upon which my biological mother’s feet must have trod one autumn afternoon of 1948. Suitcase in hand, her heart full of some mystified mixture of determination and resignation, her head still full of the blurred images of the Indiana, Illinois, Iowa and Missouri countryside flying past her train window, I can picture her trudging those three blocks up that hill, the autumn breeze in her pretty face, 25 years old, carrying within her that which was to gestate into your humble servant.

Meanwhile, back in Wichita, Harry the toolmaker and Margaret his schoolmarm wife would have been finishing up the ton and a half of paperwork necessary to adopt whichever Willows waif the baby shufflers deemed to be most

A Memoir by Galen Green

Copyright 2005, All Rights Reserved

Rough Draft; Installment #3 of 99; December 6, 2005

(Continued from Section ii. of Chpt. One: The Willows . . . . )

. . . . Waco Street near downtown Wichita, the Japanese military attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, so that Boeing Aircraft Company, where the toolmaker first earned his reputation as “The Toolmaker,” was suddenly transformed into a booming industrial complex, and Wichita began to flourish as never before – or since.

But as the toolmaker found his services increasingly in demand as part of the war effort, his schoolmarm wife found herself increasingly alone at night, while the glowing stithy of aircraft assembly hummed night and day in the furious race to respond to the very palpable from foreign fascism which was clearly hell-bent for the undoing of humankind’s noble post-enlightenment experiment in democratic government. And even though she may have kept her hands and heart busy throughout the daylight hours with the demands of teaching elementary school there in Wichita, those long lonesome nights of 1943 and 1944 and 1945, when the man she loved was far off in the darkness making the tools needed to build the B-17’s and the B-24’s and the B-25’s and the B-29’s needed to win that seemingly interminable set of overseas conflicts collectively known as World War II, served only to reinforce her longing for what she perceived to be the ascendancy unto the estate of motherhood.

And so it was that the toolmaker and the schoolmarm decided to adopt. The post-War Baby Boom helped. Every couple able to crank out a baby seemed to be doing so, whether inside or outside of wedlock. This included, of course, a certain young beautician and a forever-nameless farm boy up in some forever-nameless north-central Indiana hamlet, who got together one starlit night in the summer of 1948 to share their bodies with one another, thus setting our story in motion.

As of this writing, that three-block stretch of sidewalk which hugs the native stone retaining wall along the east edge Kansas City’s World War I Veterans Memorial Park and follows Main Street from Union Station up that hill to where the Willows once stood still consists of the very same cement upon which my biological mother’s feet must have trod one autumn afternoon of 1948. Suitcase in hand, her heart full of some mystified mixture of determination and resignation, her head still full of the blurred images of the Indiana, Illinois, Iowa and Missouri countryside flying past her train window, I can picture her trudging those three blocks up that hill, the autumn breeze in her pretty face, 25 years old, carrying within her that which was to gestate into your humble servant.

Meanwhile, back in Wichita, Harry the toolmaker and Margaret his schoolmarm wife would have been finishing up the ton and a half of paperwork necessary to adopt whichever Willows waif the baby shufflers deemed to be most

Sunday, October 28, 2007

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

What do horsemen have to offer

To times that can trample on their own?

Horsemen carved in stone

Can offer as much in human blood

As those who thundered through the mud,

Leaving us behind to survive and suffer.

What do butchers have to take

From times that sacrifice themselves?

The butcher only delves

Deep enough to rend the heart,

While we who practice the healing art

Of poetry must bludgeon it awake.

(repeat)

Words and Music by Galen Green c 1978

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

BUTCHERS CARVED IN STONE

What do horsemen have to offer

To times that can trample on their own?

Horsemen carved in stone

Can offer as much in human blood

As those who thundered through the mud,

Leaving us behind to survive and suffer.

What do butchers have to take

From times that sacrifice themselves?

The butcher only delves

Deep enough to rend the heart,

While we who practice the healing art

Of poetry must bludgeon it awake.

(repeat)

Words and Music by Galen Green c 1978

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)